Mad in Pursuit Notebook

The Conversation: Finding Samuel Newham

[Family History]

Mar. 13, 2023. “I thought you already solved that case!”

I took a drink of coffee and shook my head. Outside, snow was falling and the world was gray.

“But it’s such a great story. Samuel Newham disappears from his family some time between the birth of his fourth child Sam and the 1841 census. You find him convicted of cattle theft and exiled to a life sentence in Tasmania. I love a family rogue!”

It was a good story. Samuel Newham was the subject of a booklet: “The Good Shepherd; or, a Short Account of the Life and Death of Samuel Newham, Who Died at Somercotes, near Ross, in Van Diemen’s Land, on the 26th September, 1849.” The booklet told of a drunkard’s religious awakening and redemption under the ministry of Reverend Butters. Before his death, he was known for his piety and was pardoned of his crime.

It was a good story. Samuel Newham was the subject of a booklet: “The Good Shepherd; or, a Short Account of the Life and Death of Samuel Newham, Who Died at Somercotes, near Ross, in Van Diemen’s Land, on the 26th September, 1849.” The booklet told of a drunkard’s religious awakening and redemption under the ministry of Reverend Butters. Before his death, he was known for his piety and was pardoned of his crime.

Samuel Newham is my 3x great-grandfather, from the East Midlands of England.

“Something’s not right about it," I said. "All the records point to him being single, born of an estate owner in Nottinghamshire. No mention of being a family man. Doesn’t feel right.”

“There’s a hint.” My companion stood behind my chair as I looked at Ancestry records.

“Right.” It was an 1825 baptismal record for Sam’s daughter Jane. A notation on the handwritten record reminded me that Sam was a wheelwright by trade—a specialized branch of carpentry that made wheels and kept carriages and wagons on the road.

“That bothers me too,” I said. “Convict Sam was referred to as a ‘laborer,’ which usually means strong back, not skilled hands.”

In a column next to the baptismal record, there were several other records to check. More baptismal records. One of them was a baptismal record for Sam himself—born of Mary Hames and Edward Newham, wheelwright.

“Oh, that has to be our guy—papa was a wheelwright like Sam, not some big estate holder. Of course!”

More records about Edward and Mary clarified her maiden name as Eames, not Hames.

I continued working through the list of suggestions.

“You skipped a record,” my companion said.

“That’s a U.S. record. The Newhams all kept to their villages in the Midlands, as far as I can tell.”

He pulled up a chair and sat shoulder-to-shoulder with me. “Check it anyway,” he said.

I clicked on the U.S. Federal Census Mortality Schedules for the year ending in June 1850. The town was Jersey City, New Jersey.

There was “Saml Newham,” age 51, born in England, dead in July 1849 of a three-month bout with heart disease. Occupation: wheelwright.

What?

“That’s him! It must be him!” my companion whispered. “Look, there’s an 1840 census record.”

The 1840 U.S. Census was not very informative. It named only the head of household. But there was our Samuel Newham in Jersey City. There was a “1” under Females in Household. Hmmm.

“Maybe there’s a ship’s record?”

And so there was. On April 6, 1830, the steam-driven mail packet St. George docked in New York with about 65 passengers. On board was Samuel Newham, Wheelwright.

Just five years before, in 1825, Sam had married Charlotte Miller of Great Oakley, Northamptonshire.

Six months later, their daughter Jane was born. (I’ve stopped being surprised by “premature” babies in our family tree.) Seventeen months later, they had their son Edward. Another seventeen months—Mary Ann was born. When Sam boarded the St. George in Liverpool, Charlotte was eight months pregnant with Samuel [Jr.], my dad’s great-grandfather.

Could this really be my ancestor?

We stared at the screen. More New Jersey records popped into the suggestions column.

“Look, a will!”

It was the transcript of a will apparently written on Sam’s deathbed, July 6, 1849.

Item. I hereby direct my Executors to rent the house, shop and premises where I now reside on Newark Avenue and the lot now in the occupation of James Wilson, on Warren Street for the best price that can be got for the same, and the rent to pay over to my wife Mary during her natural life.

Item. I give and devise my house and lot on Newark Avenue where I now reside and my lot on Warren Street now in the occupation of James Wilson to my three children Jane, Mary Ann, and Samuel now living in Northhamptonshire [sic] England. To have and to hold this same to them, their heirs and assigns, equally to be divided between them share and share alike, after the death of my said wife Mary.

My heart leapt. It is himself. Those were the three Newham children I knew. And I knew his son Edward died at the age of ten, in 1838.

So, Sam left them. No mention of Charlotte in his will. (In 1841 she was supporting her children with lace making.)

Yet he was in touch—enough to know about the birth of Sam Junior, enough to know of Edward’s death. He had prospered in New Jersey and wanted his wealth to go to them.

But first…

“But first, who is this wife Mary?”

The record surfaced immediately. On November 25, 1835, Samuel Newham married Mary Kingsland in Bergen, New Jersey. A bigamist!

“Look it up,” my companion said. “I don’t think divorce was available to commonfolk in England during that time.”

“Divorce or not, that’s a harsh thing to do—to leave a pregnant wife and three babies,” I said.

“Maybe his intentions had been good. Maybe he thought he’d make his fortune in America and return home. Or send for the family. Jersey City was right across the Hudson River from New York City.”

I checked. Yes, Jersey City was a transportation boom town and teeming with immigrants.” I pulled up an old map. Newark Avenue and Warren Street were just blocks from the river.” (Click on the map below to enlarge it.)

It was time to pour myself a glass of wine. I wondered what could have been going on in England that might have driven Samuel away.

Wine poured, I found myself in the British Newspaper Archive on Find My Past. I narrowed the search down to Northamptonshire in the 1820s, but it all looked like a gigantic mass of small print.

“Search on Newham,” he said.

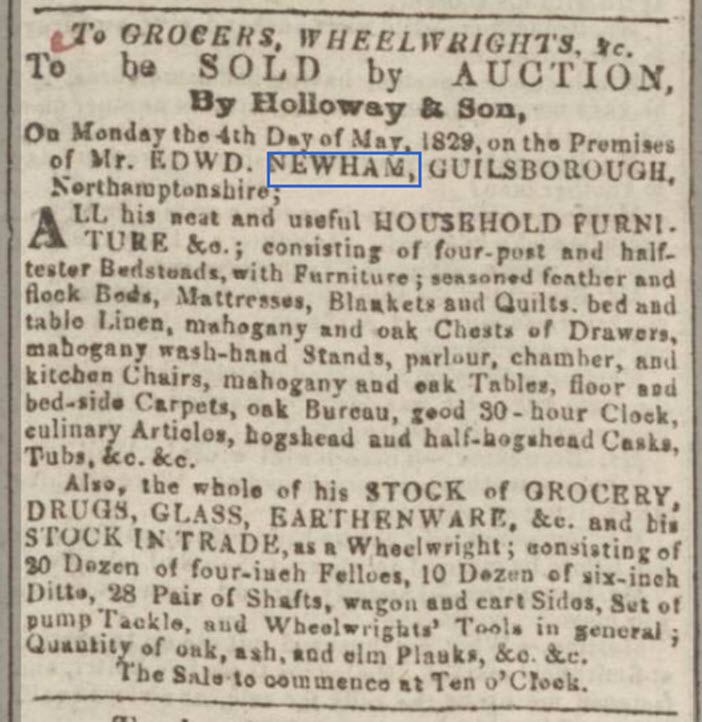

I found this: an auction. May 4, 1829. Everything belonging to Edward Newham, Sam’s father, was being auctioned off, from household to business. It appears he was not only a wheelwright but a grocer.

My goodness, I assume Edward has died. (I can't locate a record.) Sam’s brother John was the oldest son. Did he sell the business out from under Sam and impoverish Sam’s family? Or did he sell his father’s belongings to give each of the three (or more?) living brothers a nestegg? Did Sam use his inheritance to pay for his passage to New Jersey? So many questions!

As I pondered the possibilities, Jim stirred from his nap.

“What are you mumbling about over there?” he asked.

“What?”

“Who are you talking to?”

“No one,” I said.

My companion was gone. And the magic, gone with him.

***

I sit here now, wine again poured. So there were two Samuel Newhams, born six days and a few miles apart. Both of them died in 1849, at the age of 51. Sam #1 was a reformed thief, an exile-turned-religious-zealot. An interesting character to be sure. But Sam #2 is mine. Talented, skilled, ambitious, prosperous, and a cad to Charlotte and his children.

I want to know more.

FOLLOW me on my Facebook page, share this post to your friends, and....

Books from Mad in Pursuit and Susan Barrett Price: KITTY'S PEOPLE: the Irish Family Saga about the Rise of a Generous Woman (2022)| HEADLONG: Over the Edge in Pakistan and China (2018) | THE SUDDEN SILENCE: A Tale of Suspense and Found Treasure (2015) | TRIBE OF THE BREAKAWAY BEADS: Book of Exits and Fresh Starts (2011) | PASSION AND PERIL ON THE SILK ROAD: A Thriller in Pakistan and China (2008). Available at Amazon.