Walking That Mile In Another Man's Art

By Brendan McDermott

The most important lesson I’ve ever learned is that could be me. It’s a lesson in empathy, so that when I see another person doing things I consider terrible, or taking positions I consider indefensible, I’m able to take a step back and realize that through an entirely random set of cosmic variables they are who they are, and that with a different roll of the dice, they could have been me and I could have been them. Granted, I’m still human and I’m rarely able to actually take that step back in an emotional situation, but when I do, I gain a sense of perspective that I wouldn’t have been able to just instinctively reacting. It’s a powerful tool for understanding why people behave in the strange ways that they do when everything I’ve ever learned makes me think they shouldn’t be proud of their positions, that they should turn their aims elsewhere, and that they should pull up their goddamn pants. And with that in mind (mostly that last one) let’s head to Compton.

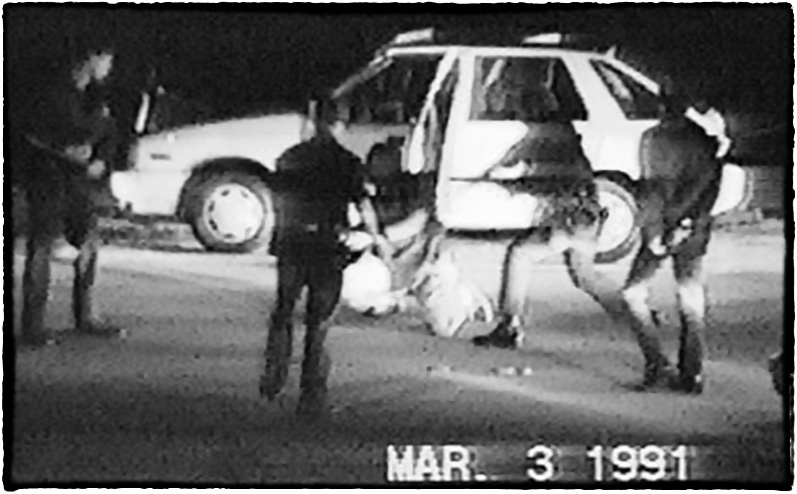

Now, Compton might not be the official birthplace of gangsta rap, but if you were to take a poll of white people in the nineties entitled “Places You Want to Avoid in America,” Compton would have a decade long dynasty. Probably longer. They saw the news reports and heard of (probably never listened to) songs called “Fuck tha Police,” or “AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted,” and decided that Compton was a terrifying cultural cesspit of gold chains and sagged pants. Then they went through their day with that opinion, and probably through their lives with that opinion. An opinion that existed unchallenged because they never asked themselves WHY “Fuck tha Police.”

Some of the best art is inspired by the worst pain. Kurt Cobain, Elie Wiesel, Kurt Vonnegut, and so many other creators took their own shapeless darknesses -- or society’s -- and shaped it into something beautiful. Art is a tool of escape, a tool of coping, an effective outlet of pain that might otherwise consume a person. Ghetto rappers are no different, whether it’s N.W.A drawing on the experience of police discrimination in “Fuck tha Police,” 2pac drawing on the misogyny in Black culture in “Keep Ya Head Up,” or Notorious B.I.G.* recounting his drug dealing days in “Everyday Struggle.” These are songs that had to made, feelings that had to be expressed, darknesses that had to be made into art, things of beauty, in order to be processed.

For gangsta rap, though, this expression, this processing of the evils around them is even more important because nobody else will tell their story. The media and the suburbs didn’t care what the hell Compton was until suddenly there was “dangerous” music coming from it. The shocking, abrasive lyrics had done their job, Compton had the nation’s attention, but at a price.

Other people are human too. So when they hear lyrics completely contradictory to their perception of truth, their instinctive response isn’t to change their perception -- it’s to reject the new evidence. The abrasive explicitness that grabbed their attention inhibits their comprehension. Rather than listening, recognizing the message of the song and the lyrical and musical talent put into making it and understanding the necessity of the graphic lyrics and imagery, they simply hear it, and take it at face value. The song suddenly goes from being provocative art to just being crude, a designation it was never supposed to have. A lack of perspective leads to a lack of empathy, and the songs are shrugged off as being “Black.”

What isn’t considered is the possibility that given the same set of circumstances, a slight tweaking in the cosmic variables of their lives, they would behave the same way. That when their truth becomes one rampant with discrimination, misogyny, and violence, they would turn to the arts, and create music that’s a raw, explicit representation of that reality? The type of music that necessitates “Parental Advisory: Explicit Content” stickers, the type of music that some people are afraid of, the type of music that’s impossible to ignore. Who’s to say that the very people and culture they rally against couldn’t very well have made by people just like them, in a wildly different set of circumstances?

Posted 7.21.2013

Brendan McDermott graduated from St. Louis University High School, Class of 2013. In the fall, he will be a student at the University of Missouri, where he will study journalism.

Brendan McDermott graduated from St. Louis University High School, Class of 2013. In the fall, he will be a student at the University of Missouri, where he will study journalism.