mad in pursuit memoir notebook

DISPATCHED FROM THE intersection of yesterday and forever

- home >

- memoir index >

- this entry

Learning Notes: Senior Year

I found a notebook from college: my senior year, 1969-70.

I am touched by the girl I see there -- the girl with the cramped and careful hand, stretching to understand things she hadn't lived long enough to grasp.

It isn't a journal. On the cover it's labeled Myth & Ritual. Most of the hundred pages or so are filled with notes for a paper on myth (a finished copy inserted between the notebook pages) and another on ritual, which I don't remember finishing, although the handwritten draft packs a wallop.

Finding the notebook was a surprise. How it survived decades of unsentimental household purges is a mystery and it's taken me a little time to piece together the intellectual landscape of a year more vividly remembered for its sexual dark side.

The beginning

It opens with some quotes from Alfred North Whitehead, such as:

The principle of progress is from within: the discovery is made by ourselves, the discipline is self-discipline, and the fruition is the outcome of our own initiative.

What follows is a page and a half draft proposal for something called the Project in Interdisciplinary Group Study. PIGS! How could I have forgotten? I wanted to form a community of learners. Whatever intellectual terrain I had tramped the year before, I was inspired to escape the confinement of supervised coursework. Tucked into the pages of the notebook is a purple-dittoed, hand-printed (my hand) grid of the schedules of all the faculty and students I'd recruited for this effort. There were six faculty, from the departments of sociology, theology, English, Spanish, and psychology and 11 students, all from my dorm floor, sophomores and juniors. (I was a senior only because I'd crammed in enough high school AP and summer school credits to finish in three years.)

Looking at those class-packed schedules, it's clear that the only one doing any independent work was me, so the project was really a bust as a community of learners. My roommate Trish had spent her summer reading the Harrad Experiment and Ayn Rand, so she was more interested in forming a community of lovers, which was a different kind of failure. The other girls-to-women were good students but afraid of losing credits somehow if they strayed from what was prescribed for them.

The faculty who "signed on" didn't lift a finger to help but didn't interfere either. They always seemed to stand back and let me do whatever I wanted. (One, maybe two of them turned out to be more interested in Trish's community of lovers.)

The irony is that by the end of that school year, everything had busted wide open. The faculty were throwing out all the curriculum requirements in a big series of meetings in which relevance was the buzzword of the day. Then, halfway through the third trimester, the National Guard killed 4 student demonstrators at Kent State and all the curriculum and schedule nonsense stopped cold. We were in "alternate university" mode, instantly a community of so-called learners…

But I'm getting ahead of myself.

Mundelein was a Catholic women's college, of solid quality, but still basically a commuter college for girls with aspirations to be teachers while they raised their families. Even in the dorms, about half the students were 5-day residents who went home to mom and dad on the weekends. It was a long way from Berkeley.

But for me, Mundelein was as far as I could get from home without money. The nuns had given me a scholarship and work-study jobs. I studied Spanish and Portuguese literature and longed to be cosmopolitan. I stopped being a Catholic. No crisis. No agonized decision. No arrogant pronouncements. I just took it off and put it away.

But at the same time I opened up to the study of myth and ritual and the unifying potential of the religious experience. Joseph Campbell's Hero with a Thousand Faces became my Bible.

Of course, I wouldn't know a religious experience if one came up and bit me. I didn't even do enough drugs to lay claim to one (unless you count the transcendent thrill of being felt up by an assistant professor after too many glasses of sangria). My notebook tells me that I was searching for the equivalent of myth and ritual in a post-religious world.

I loved mastering the vocabulary as much as anything. Numinous, mythopoeic, ontological. And I also labored to make my capital Cs and Hs curve in the gracious European manner of the Spanish professor I had a crush on.

I skittered across the surface grasping to understand Martin Buber and Mircea Eliade.

There is a note to myself at one point, to check the validity of using literary examples in explicating theological, sociological, or philosophical themes. After struggling to grasp the philosophical stuff, I always came back to literature. Not only stories, but the story-making experience. That year, I read everything Elie Wiesel wrote and pondered the "ritual" of his telling and re-telling the story of his Holocaust experience. Then I read everything Kurt Vonnegut wrote. He had been writing for years but had just published Slaughterhouse Five, the first story about his prisoner-of-war experience and the horror of the Dresden fire-bombing. It impressed me that he needed to tell a dozen tales before the most important one could emerge.

I was way over my head trying to find the intersection between religion and sociology and literature. My notes jump all over the place showing no systematic line of inquiry. I can't recall anyone mentoring me. (I can't even remember who I was supposed to be submitting the papers to.) But I look through it now and am still fascinated with all I was trying to understand.

I began the year with little life experience, although I clearly longed for it. During that year I filled my head with a stew of ideas about some of the most profound areas of life. While I filled my notebooks and wrote my papers, boys were being shipped off to invade Cambodia. A dear and influential teacher was dying a slow death from liver cancer. The more she suffered, the faster I consumed all the Elie Wiesel books I could find. While I gave up on the community of learners and joined the community of lovers, I took diligent notes from books on the loss of the myth of American innocence:

Hero: sensitized outsider, marginal man, seismographic schlemiel, who, "experiencing in magnification the sin & the guilt of his contemporaries, sacrifices himself quixotically for their redemption or performs an exemplary spiritual passage for his own salvation (or fails painfully in the attempt). Though generally not religious in a traditional sense, a large number of our recent novels are almost paradigms of the existential possibilities (& impossibilities) of sainthood."

The end

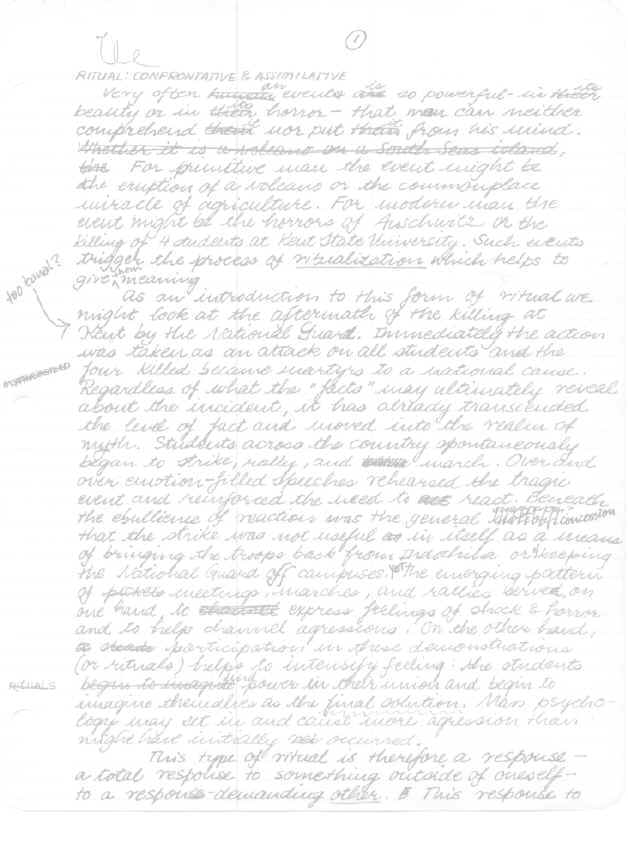

I look now at the essay I drafted on ritual. I'm sure it was never typed and handed in because schoolwork was irrelevant in June, 1970. Nevertheless, consistent with my yearlong study and in my best composition style, I wrote the following:

Very often an event is so powerful — in its beauty or in its horror — that man can neither comprehend it nor put it from his mind. For primitive man the event might be the eruption of a volcano or the commonplace miracle of agriculture. For modern man the event might be the horrors of Auschwitz or the killing of 4 students at Kent State University. Such events trigger the process of ritualization which helps to give them meaning.

As an introduction to this form of ritual we might look at the aftermath of the killing at Kent by the National Guard. Immediately the action was taken as an attack on all students and the four killed became martyrs to a national cause. Regardless of what the "facts" may ultimately reveal about the incident, it has already transcended the level of fact and moved into the realm of myth. Students across the country spontaneously began to strike, rally, and march. Over and over emotion-filled speeches rehearsed the tragic event and reinforced the need to react. Beneath the ebullience of reaction was the general concession that the strike was not useful in itself as a means of bringing the troops back from Indochina or of keeping the National Guard off campuses. Yet the emerging pattern of meetings, marches, and rallies serve, on one hand, to express feelings of shock & horror and to help channel aggressions. On the other hand, participation in these demonstrations (or rituals) helps to intensify feeling: the students find power in their union and begin to imagine themselves as the final solution. Mass psychology may set in and cause more aggression than might have initially occurred…

In the margin there is a note to myself, with an arrow to the Kent State passage. It asks, too banal?

I don't know why this notebook survived. It wasn't a journal because it didn't record anything that happened to me or capture what I felt about anything. It was simply the notes of a 1969 college girl who wanted more than anything to be in charge of her own learning.

9.19.99