mad in pursuit travel notebook

DISPATCHED FROM THE CROSSROADS

- home >

- travel index >

- ireland 2012 >

- today's entry

Ireland Highlights, #1

PHOTO: Back L-R: Maura Stephens [Kilmartin]; Siobhan O'Neill and her mother Ann O'Neill, Mary Mahoney [Grett Stephens]; Helen Collins [Mike's daughter]; Ann and Caithriona McLoughlin. Front L-R: Cora Monaghan; Maureen Collins; Jim Z; Mick Dunne; Mike Collins. Maureen, Mick and Mike are my dad's first cousins. The others are my second cousins (Siobhan, once removed). Taken at the Malt House in Mountbellew on our last night there -- an informal farewell. 17 May 2012.

What I loved about Ireland was being welcomed home. That's deep. That's being connected over long times and far places. That's family.

Going to Ireland feels like falling. Isn't that funny. I feel like I'm falling through the sky -- not flying -- I'm face up, arms and legs outspread, letting go, falling into the heartland -- like Dorothy falling back into Kansas.

In the U.S. we love being Irish -- it's about big Catholic families, parochial schools, drinking prowess and St. Patrick's Day. In Ireland, the returning daughters of émigrés find being Irish is, first of all (of course), about economics, politics, and the balance between the traditional culture and the modern European. But then it is also still about diaspora, unjust hunger, and the fight for freedom. Just as the American Civil War created a bloody gash across our 19th-century mental landscape, so did án Gorta Mór -- the Great Hunger (1845-1852). It changed everything.

Before our first trip in 2007, I was dying from anxiety about meeting the cousins and living up to the jolly conversational standards set by my parents and sisters before me. But I discovered that being the nerdy one puzzling over the family tree gave me an in. It's a truism that people love talking about themselves but they also don't mind talking about us -- how we are connected, how we are family. So I've embraced my role as the one who writes things down -- the curious story collector.

Before our first trip in 2007, I was dying from anxiety about meeting the cousins and living up to the jolly conversational standards set by my parents and sisters before me. But I discovered that being the nerdy one puzzling over the family tree gave me an in. It's a truism that people love talking about themselves but they also don't mind talking about us -- how we are connected, how we are family. So I've embraced my role as the one who writes things down -- the curious story collector.

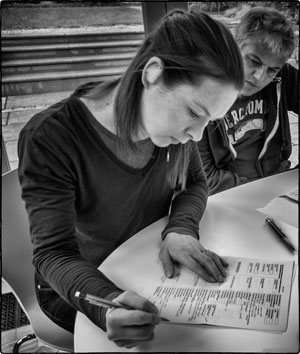

[PHOTO LEFT: Doréne Divilly takes her turn correcting the family tree, with her husband Colm looking on. Dublin, 7 May 2012]

One of the most moving things I did was to walk on the land where my great-great-grandparents John Martin and Bridget Ward had their cottage during the 19th century. From old maps and census data, I had pieced together its approximate location in Rushestown. But then Maureen Collins found Pakie Kenny, whose family has been continuously in that village and were neighbors of the Martins. Kenny is in his sixties, with white hair and clear blue eyes. His cattle graze in the field where the Martins once lived. We walked around and imagined the family gathered around their fire after a hard day's work. We looked up and down the slope and tried to see the landscape through their eyes. The Irish speak of "thin places," where the loving past can speak to those who listen. This was one of those places.

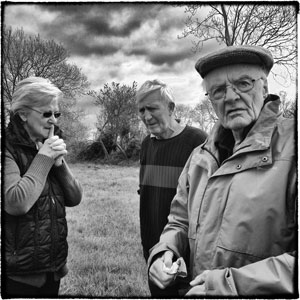

[PHOTO RIGHT: Maureen, Pakie, and Jim on the old Martin land in Rushestown, County Galway.]

From Rushestown, we continued our pilgramage through New Forest (where the D'Arcy landlords lived), past the Curraghmore National School (where my grandmother and her siblings learned to read, [photo below]), and through the village of Ballaghduff, where my grandmother was born and raised. Maureen was an ideal guide because she too was born on the farm in Ballaghduff and started her schooling at Curraghmore. She showed us the break in the stone fence they all used as they crossed the immense pastures from village to school each day. She is a bridge between the families who worked these hardscrabble farms and the modern Irish woman, educated and worldly.

I came away with an insight. On the old family lands I didn't experience God, angels, fairies, or the spirits of ancient druids. I did feel the presence of Those Who Loved Us -- the hardworking people who, together, kept their families warm and fed and who made sure their children were educated. And, who, when the time came, held going away parties, packed belongings on carts and drove their young adult children to the train station to say goodbye, knowing that all they might ever see of them again was a little cash to help out, some used clothes, and maybe a ticket to America for another sister or brother.

[PHOTO BELOW: Curraghmore National School, a two-teacher schoolhouse, which provided primary education to the children in the surrounding rural townlands for over a hundred years, 1860-1977. School was taught in the Irish language.]

May 25, 2012